p. 463: Participants of the trip to the Franciscan Monastery at Kostanjevica near Nova Gorica on 12 May 2010. Astronomy group within the U3A programme (University for the Third Period of Life).

Photo: Zorko Vicar

Two articles by Zorko Vičar for the Slovene astronomy magazine Spika (excerpts from the articles)

1) November 2010

The Franciscan Monastery at Kostanjevica has preserved classical and medieval astronomy for centuries (p. 464)

We never dreamt that we would list through almost 800-year-old university textbooks on astronomy, forgotten behind monastery walls in Slovenia.

We came to this unexpected opportunity in a slightly roundabout way. At the professional meeting "Slovenia and the universe: past, present and future", Dr Vida Žigman (University of Nova Gorica) surprised many with the news that the Franciscan Monastery at Kostanjevica has a Latin reprint (dated 1635) of Galileo's "fateful" book In quo Quatuor Dialogis, de Duobus Maximis Mundi Systematibus, Ptolemaico & Copernicano. The book was first published (in Italian) in 1632 with the permission of at least four censors. Thus it was not a simple matter in 1633 to bring an accusation against Galileo. But because of the book and other so far unexplained circumstances, Galileo ended up under house arrest, and also had to recant his proposition about the Earth's movement as the only correct one. The matter was concluded, at least legally, in Galileo's favour only by the Polish pope, Karol Wojtyla, in 1992. The information that this important book exists in Slovenia was sufficient reason for us astronomers from Šentvid /a suburb of Ljubljana/, together with members of the U3A Astronomy group, to visit the monastery in May 2010.

Following my enquiries, the very friendly monastery librarian, Ms Mirjam Brecelj, invited us to visit the monastery, its library and the tombs of the Bourbons, the family of the last king of France. None of the young participants, nor many of the older ones, knew that the last French king as well as a grand-daughter of Maria Theresa, daughter of the famous Marie Antoinette (the French queen beheaded during the French Revolution in 1793, who reputedly declared, "Let the people eat cake if they don't have bread") were buried in Slovenia. Whether we ought to know these historical "trifles" is another matter!

Ms Brecelj also wrote that she had found in the monastery catalogue as many as 53 items under the heading Astronomy (ranging from 1553 to 1929), that some of these books were very richly illustrated – and still comprehensible today. Incredible! Even more – she sent me the astronomy section of the catalogue. Here of course was the book mentioned above – Galileo's in the Latin reprint of 1635. For me this was the first mystery – Galileo under house arrest, but his book published in Latin two years after he was accused. Probably there is some simple explanation for this reprint – but I haven't yet managed to find any. Neither I nor other colleagues had much time to study the whole list, so I selected some books about 450 years old and looked for basic data on these authors and their writings. Within a few hours I had slipped back into the Renaissance, the Middle Ages, classical times. The list also included the medieval author Sacrobosco with his textbook Tractatus de Sphaera. This was written c. 1230; the reprint held by the monastery was dated 1561.

I sent this hastily gathered information to Ms Brecelj and received a swift answer: "If we two co-operate a bit more, I'll be borne among the stars as well! So much data, and so interesting... This really is the charm of a library and books – when you fall into them, you can't climb out! Since you mention Sacrobosco, another of his books was recorded in the library – Spaerae mundi, an incunabulum of 1488, but it is listed among missing books and so far has not been found."

Fine thoughts indeed, and "crazy" news about this book from 1488. This was the first printed book about astronomy in the world and is just another title for the original Tractatus de Sphaera of 1230. It is reported to have had more than 30 incunabula (i.e. works printed before 1500). The monastery library had some of these listed after the Second World War, but where are they now?

The author Johannes de Sacrobosco or Sacro Bosco (John of Holywood, born c. 1195 in what is today Artane, a suburb of Dublin, died c. 1256 in Paris) was an Irish scholar, monk and astronomer. He studied in Oxford, taught at Paris University, and c. 1230 wrote the finest medieval textbook on astronomy, Tractatus de Sphaera. This was used for 400 years by practically all the European universities right up to the 17th century. Sacrobosco discusses the Earth and its place in the universe. The basis for the explanations was Ptolemy's Almagest – geocentrism. With arguments that are still valid today, Sacrobosco's description and sketches of the Earth as a sphere undermine the 19th-century error that medieval scholars taught that the Earth was flat. Many still perpetuate this 19th-century folly in our schools, but why? The lie derives primarily from Washington Irving's book Christopher Columbus and his Journeys (1828), but other factors could be found, such as ideological reasons. What should be done with historical lies so that they don't become "truth"? In 1945, for instance, this particular lie about the so-called flat Earth held second place among the 20 most frequent historical lies, a list constructed by the Historical Association of Britain.

Sacrobosco also knew the mistake in the Julian calendar and proposed (in his book De Anni Ratione of 1235) a correction whereby one day would be omitted every 288th year. Later on the Gregorian calendar (Gregory XIII) took account of this correction – but did so immediately. In 1582 the month of October was shortened by 10 days, so that the date 4. 10. 1582 (Thursday) was followed by 15. 10. 1582 (Friday).

A summary of the contents of the textbook Tractatus de Sphaera, pp. 465-467

/Last paragraph, p. 467/

These are some of the emphases in Sacrobosco's medieval textbook on astronomy. There were many copies and then reprints of the original, to which editors added new passages, corrections, and sometimes mistakes as well (in later reprints, for example, there is a mistake concerning the number of days in the year but this is most likely just a printing error). If we exclude the false geocentric picture of the universe, most of the assertions, conclusions and measurements are correct or nearly correct. In order to explain celestial mechanics correctly they made use of the geometry of circles (epicycles, equants, deferents).

Captions to photographs

p. 463: Participants of the trip to the Franciscan Monastery at Kostanjevica

near Nova Gorica on 12 May 2010.

Astronomy group within the U3A programme (University for the Third Period of Life).

Photo: Zorko Vicar

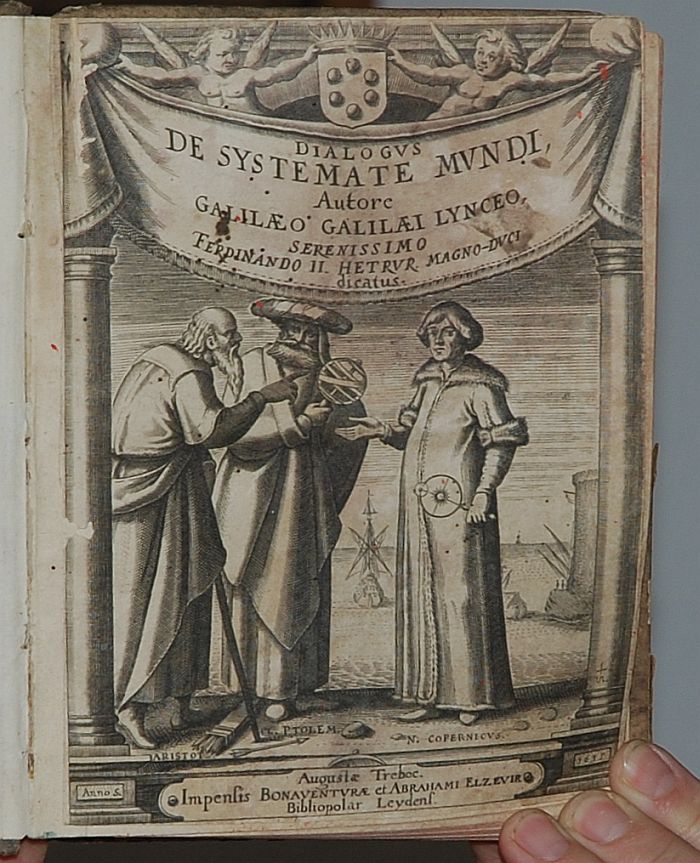

p. 464 bottom left: An illustration from Galileo's book In quo Quatuor

Dialogis, de Duobus Maximis Mundi Systematibus, Ptolemaico & Copernicano of

1635. The three men are Salviati (representing Copernicus' doctrine), Sagredo (an

educated citizen) and the awkward Simplicio (representing Ptolemy's old view of

the world). It is not known exactly why the pope, who at first encouraged Galileo in

his writing, then turned against him. It seems that some convinced him that Simplicio

(awkward and conservative) was actually a picture of the pope. Others suggest

that Galileo was a victim of jealous Jesuits, because he didn't mention Brahe's

model of the Solar system. Photo: Zorko Vicar

top right: Ms Mirjam Brecelj (with a book in her hand) presents the oldest

astronomy books in the Kostanjevica monastery - Slovenia's hidden treasures. The

books selected have survived turbulent centuries, wars, earthquakes, mice in hiding

places (put in barrels during the First World War), mould, human folly, etc., and have

waited for "us". Let's see to it that such books will be restored, preserved for posterity

and that we will learn something from them. Our thanks to Ms Brecelj for her kindness

and the work she put into arranging our visit and communicating information, thus

providing us with an exceptional experience, seeing a real picture of classical and

medieval astronomy. (Perhaps these books will bring pleasure to others in Slovenia.)

Photo: Zorko Vicar

2) Spika, December 2010

S P I K A,

pages 510 - 513, Spika 12 (2010)

Fragments from the history of celestial mechanics

Many today consciously or carelessly pooh-pooh the classical picture of the universe – but it's interesting that sometimes the same arguments and logic itself show that both the classical and modern pictures of the universe are correct. The most obvious example is the phenomenon of parallax – the apparent movement of nearby stars in relation to their starry background on account of the Earth's movement around the Sun. We observe parallax if a nearby object is looked at alternately with the left eye and the right eye and it apparently moves in relation to its background. Parallax also allows us to see in depth – 3D observation. The first instrumental parallax of a star (and thus the distance to the star, with the exception of the Sun) was determined by Friedrich Bessel in 1838 for the star 61 Cygni (it amounts to less than a parallax second, only 0.3", which is far below the eye's ability to distinguish, which is about 60"). This was one of the last proofs that the Earth orbits the Sun. The GAIA project of the European Space Agency, which measures the distance to the stars in our galaxy, uses just the same principle – parallax. Slovenes are also involved in this project through the Department of Physics, Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, University of Ljubljana. But because Aristotle could not observe parallax of the stars, since in classical times they had no telescopes, and with the eye it is not possible, precisely this was his argument that the Earth doesn't move – if it moved, parallax would be observable. So here Aristotle was true to the scientific method. Of course we could argue that "he could have considered" that the stars are so far away that their parallax is not perceived by the naked eye. But such a route, projecting the present into the past, can lead to inappropriate speculations (this comes easily to us but is often unproductive).

For the sake of truth and historical balance it should be stressed that many classical thinkers (the Pythagoreans Hiketes, Ecphantus, Heraclides Ponticus, etc.) were convinced that Mercury and Venus orbit the Sun and thus the conclusion of some contemporaries that perhaps the other planets also orbit the Sun. Later the Greek Aristarchus described the heliocentric as well as the geocentric model of the universe. In the heliocentric model he accepted that the stars are indescribably far away since no parallax can be detected, i.e. the movement of stars in relation to each other during the Earth's orbit around the Sun. The Greek Apollonius tried to harmonize Aristarchus' and Eudoxo's ideas on the movement of the planets with the new model (the problem was the epicycles for Venus and Mercury), where the planets orbit around the Sun, while that, together with the planets, orbits the Earth.

A similar solution was given much later (in the 16th century) by the Dane Tycho Brahe. The Frenchman Nicole Oresme (14th century) had very penetrating thoughts, saying that it would be more "economical", understandable, that the small Earth revolved around its own axis rather than that a huge sphere, studded with stars, should orbit the Earth. This deduction probably rested on estimations of the size of stars and the distance of the so-called sphere or spheres. Nevertheless he concluded that none of these statements was sufficiently convincing and said, "Everyone maintains, and I think myself, that the heavens do move and not the Earth." A scientific position can be seen here, the significance of the convincing nature of arguments, but at the same time, also how much power a generally accepted explanation has (sight, feeling, the flow of the crowd), even though wrong. The German Cusanus (15th century) said that the Earth turns around its axis and orbits the Sun, that there is no "above" or "below" in the universe, that the universe is boundless, that the stars are other suns and attach to themselves other inhabited worlds. Most of these above-mentioned reflections of classical thinkers, partly also of medieval ones, were known to Copernicus. Heliocentrism as a possible picture of the universe was thus allowed even before Copernicus. To recap some of the names: the Greek Aristarchus (classical period), the forerunner of relativity the Frenchman Oresme (14th century), the German Cusanus (15th century) and still "many" others. But we shouldn't create illusions – most people (educated as well as uneducated) naturally rejected the possibility of daily rotation and the Earth's orbiting the Sun. Why? Because they had the experience of their own rotation, of movement on the Earth (for example, on horseback, on a ship), which caused air resistance (wind) and this was one of the main arguments against the daily rotation of the Earth and its movement around the Sun. Another difficulty was that of Hipparchos, saying that if the Earth really rotates, then an object which we throw up into the air should remain there. Today these arguments probably sound ridiculous, but for the level of natural science at that time, they were quite convincing.

Sacrobosco, the Royal Society, errors

At the end of May 2010 some from our Astronomy group travelled to London. The visit turned out to be a real surprise – perhaps something about that another time. Why do I mention this excursion? We visited the Royal Society (this year celebrating its 350th anniversary), where Mr Rupert Baker (Library Manager) courteously received us. For all of us this visit to the Royal Society was something special. On that occasion I asked Rupert Baker about medieval textbooks on astronomy – with my special interest in Sacrobosco. He immediately responded that certainly they have the book Tractatus de Sphaera, the medieval university textbook on astronomy by the famous writer and scholar Sacrobosco. This was yet another affirmation of the value of books – what we have in Slovenia is hidden to the eyes and awareness of Slovenes – why?

It should be stressed that it was precisely the astronomer Halley (with whom Valvasor regularly corresponded) who presented to the Royal Society a physical model of the intermittent lake Cerkniško jezero, of course according to Valvasor's sketches and descriptions. Valvasor died some years before Halley's visit to Slovenia, so their desired meeting never came about. Between 1701 and 1703 Halley made a number of visits to Ljubljana, Trieste and other places in this region with the secret mission of searching for a suitable harbour for the English navy (the reason being the Spanish War of Succession). This idea was never realized – after a successful attack by the English and Dutch on Gibraltar in 1704 it was completely abandoned.

We were specially shown the written description of Robert Hooke's appearance instead of a painting – why no picture? The answer follows, but first here is the description of Hooke: "He was always very pale and lean, … with a meagre aspect, his eyes grey and full, with a sharp ingenious look whilst younger; his nose but thin, of a moderate height and length; his mouth meanly wide, and upper lip thin; his chin sharp, and forehead large. " Richard Waller, Hooke's friend.

I myself had put the supposed portrait of R. Hooke on the web (along with the description of our trip). This was noticed by Rupert of the Royal Society and he pointed out to Margaret and me the mistake whereby the chemist Jan Baptist van Helmont had been confused with Hooke. How did this error come about? Rupert sent a very interesting article from The Guardian about famous men and women and their "lost" portraits. Some extracts from the article "Mistaken Identities", by the author Lisa Jardine: "In 2002 ... wrong identification of the portrait on the internet."

Certainly a big quandary for Ms Jardine, which shows how quickly we fall into a trap, with what difficulty we get out of it and how we remain alone after the mistake is discovered. There are an enormous number of such mistakes on the internet, and the Slovene version of Wikipedia still has under the entry R. Hooke a portrait which is not of him but of the chemist Jan Baptist van Helmont. Hooke really doesn't have any "luck" – even if by chance some portrait still exists and someone should find it, that person would probably think a thousand times before revealing this to the public. See also http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Van Helmont. May this text also be a modest help to Ms Jardine in dispelling "her" mistake.

Thanks to those known and unknown persons who cared for the written word

Let us return to the library of the Franciscan Monastery at Kostanjevica near Nova Gorica.

The monastery library also holds some basic works on the Slovene language. For example, one of the eight extant copies of the Slovene grammar written in Latin, Arcticae horulae succisivae, published by the Protestant Adam Bohorič (Adamus Bohorizh) in 1584. He introduced the type of alphabet named after him bohoričica, used by France Prešeren /the greatest Slovene poet/. Prešeren defended the bohoričica, but the Illyricists abolished it. We feel the consequences even now but it is interesting that a new bohoričica has been introduced. It is used by some IT people, since it resolves the constant problems with fonts. Also one of our literary periodicals is published in bohoričica. The linguist Father Stanislav (Anton) Škrabec also worked for 40 years in this monastery. Some consider him the greatest Slovene linguist of the 19th century.

Like many other monasteries, this one at Kostanjevica preserved the basic works of both native and foreign writers in the humanities and the natural sciences. It won't come amiss to mention the Žiče monastery either. This Carthusian foundation would have celebrated its 850th anniversary this year if Joseph II hadn't dissolved it in 1782. At the turn of the 14th/15th century, when Europe was shaken by religious and political conflicts, Žiče was the centre of the eastern order of Carthusians. From the Carthusian monastery the prior general Štefan M. (also because of Catherine of Sienna) pacified and drew together a divided Europe. This sounds quite up-to-date. Štefan succeeded in his mission. In the 15th century this monastery held over 2000 books – almost as many as the Vatican library had, and that is one of the largest in the world. Now these books are scattered around different monasteries and libraries. It would be good to survey this rich treasure from the standpoint of natural science as well.

Captions to photographs

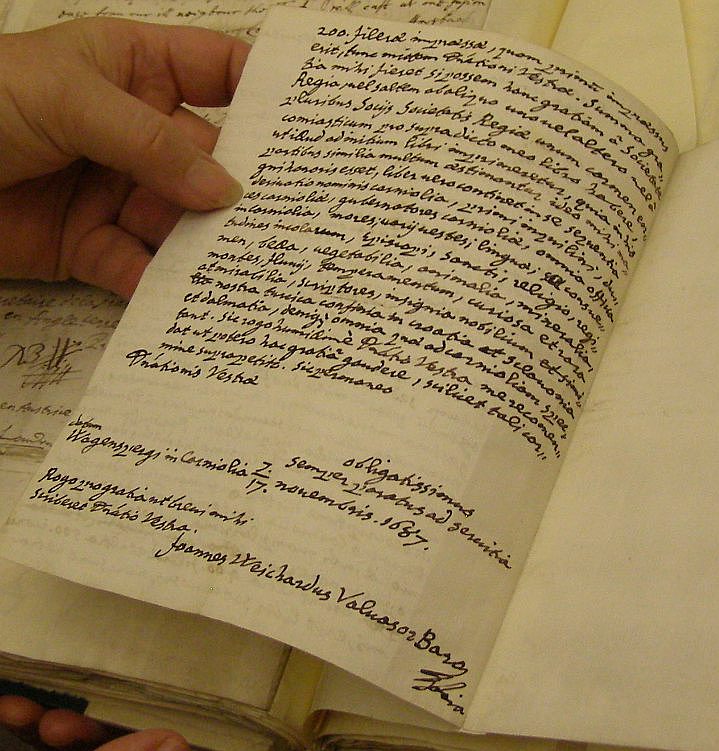

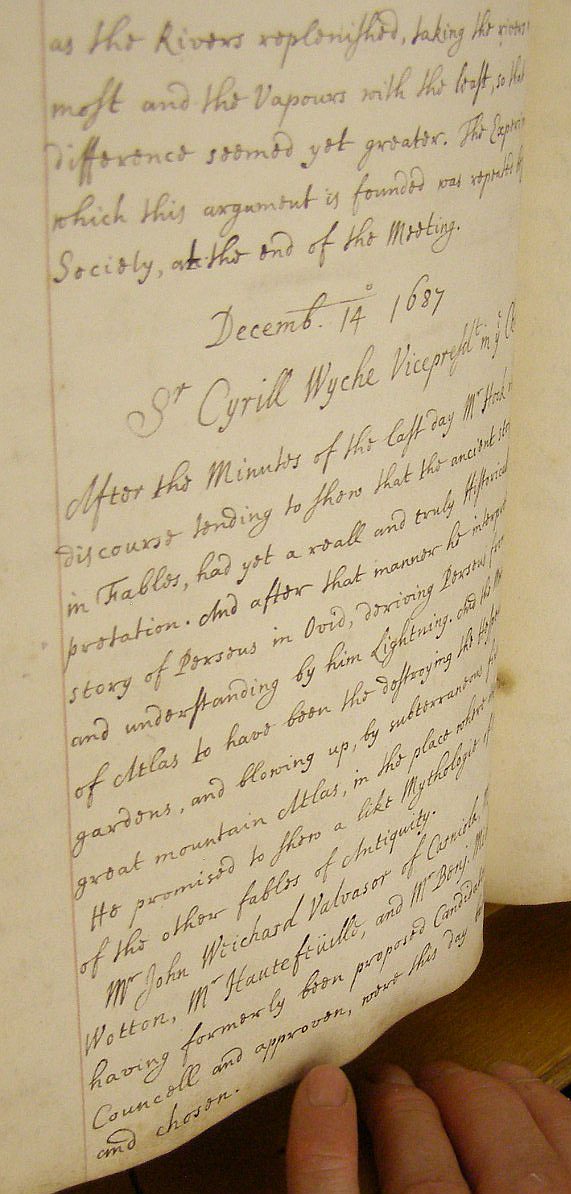

p. 510: Just as Ms Mirjam Brecelj, the Kostanjevica librarian, was extremely

friendly, so was the archivist Ms Joanna Corden at the Royal Society. Together with

Rupert she showed us treasures from Valvasor's intellectual legacy (Valvasor

became a member of the Royal Society in 1687) – the originals of his treatise on

being received into the Royal Society, sketches of the intermittent lake, Cerkniško

jezero, the minutes concerning his reception (see photos of the documents on the

following page. Published with the permission of the Royal Society). Photo: Zorko

Vicar

p.511: The texts are readable and understandable. (Published with the

permission of the Royal Society)

Photo: Zorko Vicar

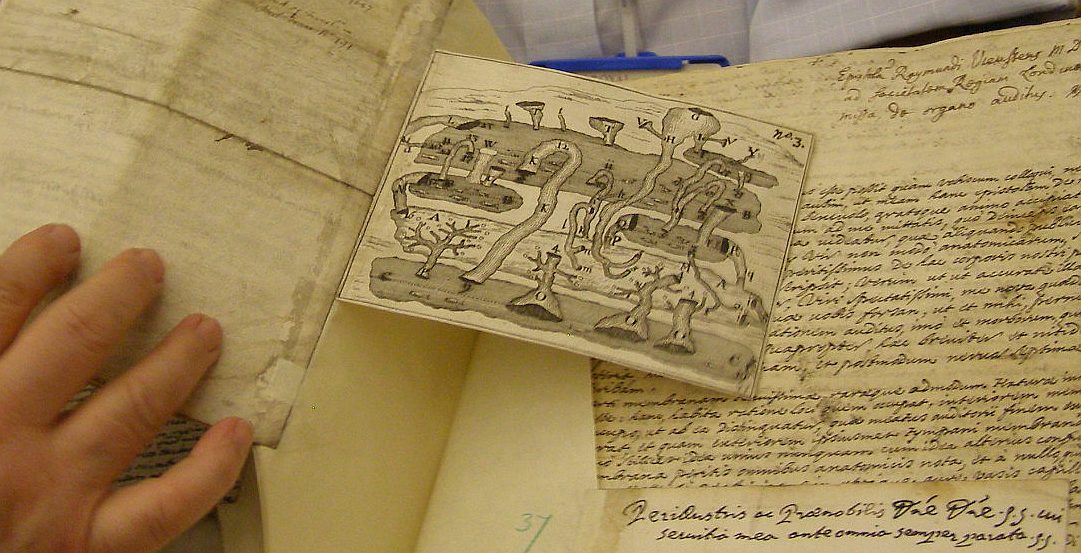

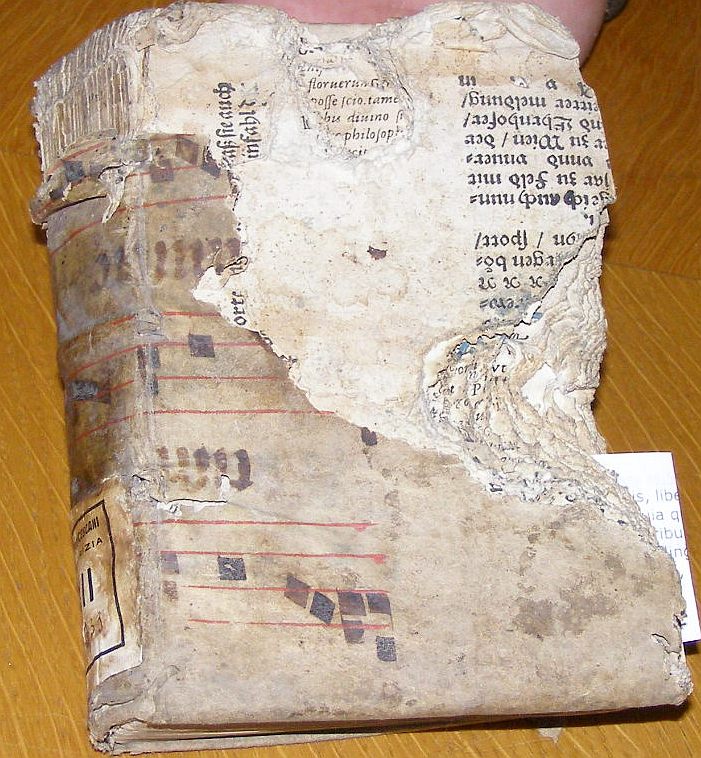

p.513: An eloquent picture of the decay of our invaluable cultural and

scientific heritage. Centuries ago the book was wrapped in a medieval music

transcription and both proved very appealing to mice. These books were hidden in

barrels in cellars during the First World War (the appalling Isonzo front). A very

praiseworthy action, since in hard times most people forget about saving books.

Photo: Zorko Vicar

Ljubljana, November, December 2010, Zorko Vičar

Translated by Margaret Davis

Source of the images (some abstracts), where is not my name, is:

http://pages.cpsc.ucalgary.ca/~williams/Full%20text%20items%20from%20the%20

tomash%20Library%20files/Sacrobosco,%20Johannes.Spaerae%20mundi.1488.Venice

.pdf

Back.